Planning and Conducting Workshops

What Is It

Definition

A workshop is a process where two or more people, under the guidance of one or more facilitators, go through a series of planned and ad-hoc activities to solve a particular problem or to reach a particular actionable goal.

A workshop is about getting things done, be it finding a solution to a problem, or reaching a decision to move forward.

Core Concepts

It’s important to differentiate several core concepts, even though we sometimes use some of them interchangeably in various contexts:

| Activity | Discussion | Session | Workshop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structured sequences of talking, writing, drawing, acting, and making. Often led by one or more facilitator(s). | Two or more people talk, without going through any activity. | One or more person(s) talk, and go through planned or ad-hoc activities when necessary. | Two or more people engage in a sequence of planned and/or ad-hoc activities. |

There’s no clear-cut between any two of them, while generally speaking, workshop is more formal and specialized than session, session more than activity, and activity more than discussion.

Five Types of Workshops

There are five types of workshops common in a project setting:

- Discovery workshop: understand current state and build consensus for future plans

- Empathy workshop: understand the needs of the respective audience (e.g. end users)

- Design workshop: generate ideas for solving a problem

- Prioritization workshop: establish focus in building a solution

- Critique workshop: analyze and improve a solution

Although a workshop is often associated with a design process, it’s not exclusive to the design practice.

Context

Workshop vs. Meeting

A workshop differs from a meeting in its purpose, scope, length, structure, and preparation.

| Workshop | Meeting | |

|---|---|---|

| What | Things get done. | Things get discussed. |

| Purpose | Decision making or consensus building to achieve an actionable goal. | General knowledge sharing and status update. |

| Scope | Deep, focused coverage of a particular issue. | Shallow coverage of many topics. |

| Length | Measured in half-days or days. | Measured in half-hours or hours. |

| Structure | Active participation in making decisions and doing things. | Conversation-driven listen and talk. |

| Preparation | Includes getting buy-in, creating agenda, preparing materials and tools, design activities, etc. | Focused on meeting outline and presentation. |

When to Use

Workshop in General

“Misused workshops are a waste of time.”

A workshop is almost never a good starting point to engage stakeholders, clients, or target audiences.

The most effective workshops emerge naturally, out of necessity, during the continuous engagement with them.

Consider implementing a workshop only when:

- There’s a clear, achievable goal

- There’s consensus on that goal

- There’s already some level of buy-in from the target audience

- There’s basic level of trust among facilitators and target audience

- General knowledge sharing has already happened

- There’s a willingness to go deeper into a particular issue

To meet any of the above conditions, consider conducting interviews or meetings, and take time engaging with your target audience through discussions and work sessions.

There’s a huge difference between interacting with someone you barely know and interacting with someone you’ve become familiar with.

In general, workshops are more effective and efficient in the latter case.

That is not to say that we cannot conduct workshops with stranger participants—while they may be complete strangers in any official sense (e.g. we may have never worked, directly or indirectly, with them before), a certain level of familiarity can always be achieved through the engagement leading up to the workshop. Social connection matters. Even when the participants are complete strangers to us, we can still help them become comfortable and even familiar with us before the workshop.

One might suggest that an ice-breaking activity, such as introducing each other through casual chats or games, would address the above issue, while a genuine sense of familiarity doesn’t solely come from knowing people’s names or backgrounds; it also comes from social interactions. As Batman says in a film: “It's not who I am underneath, but what I do that defines me.”

What we do and how we engage our workshop participants before the workshop have a non-trivial impact on the quality of the workshop.

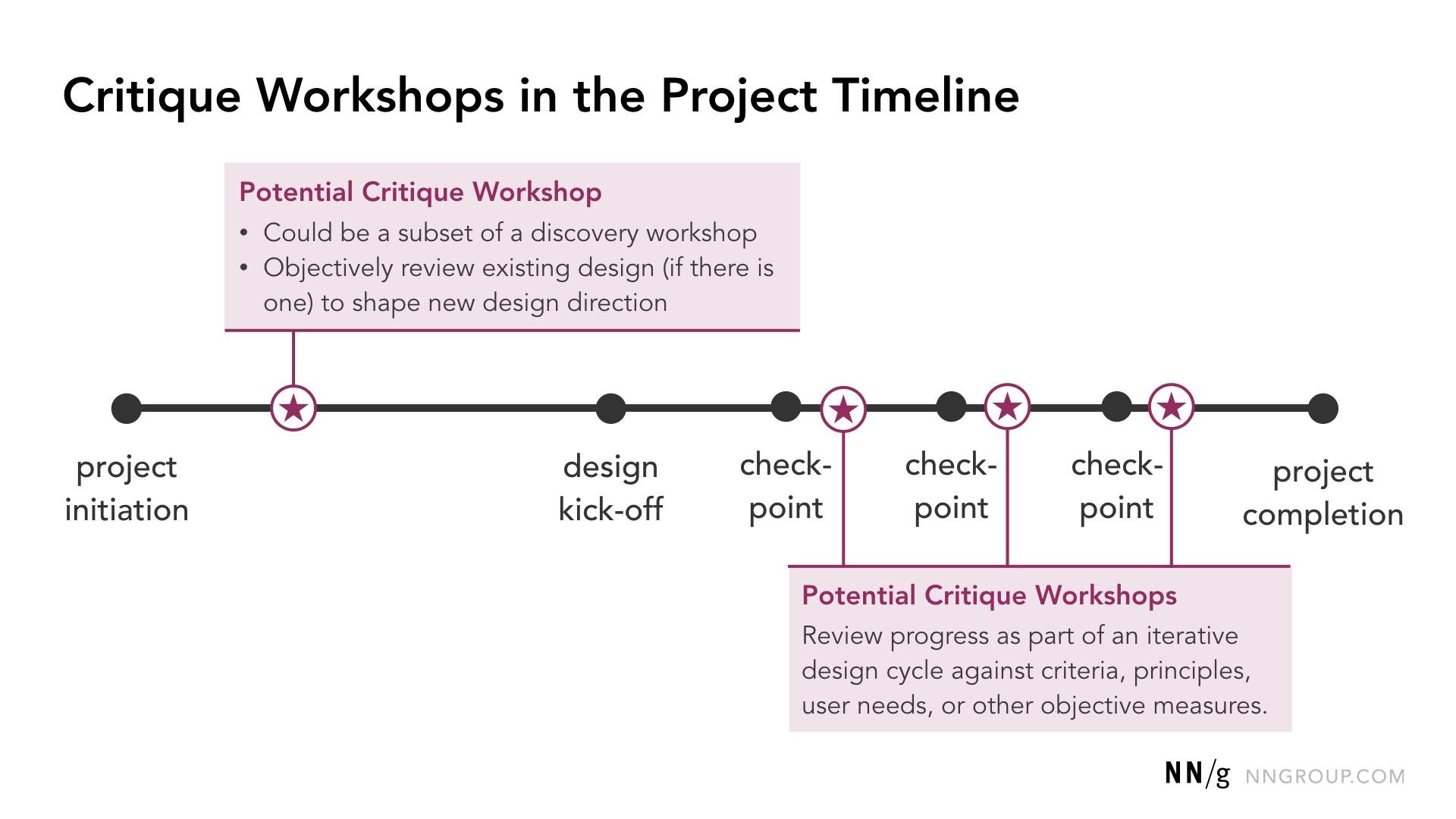

Workshop in Project Process

Although workshops are likely famous for its use in early stages of a project (you might be familiar with such jargons as “discovery”, “initiation”, “concept case”, or, my oh my, “Design Thinking”), different types of workshops can benefit us at various stages of a project.

Nielsen Norman Group summarizes the big picture perfectly:

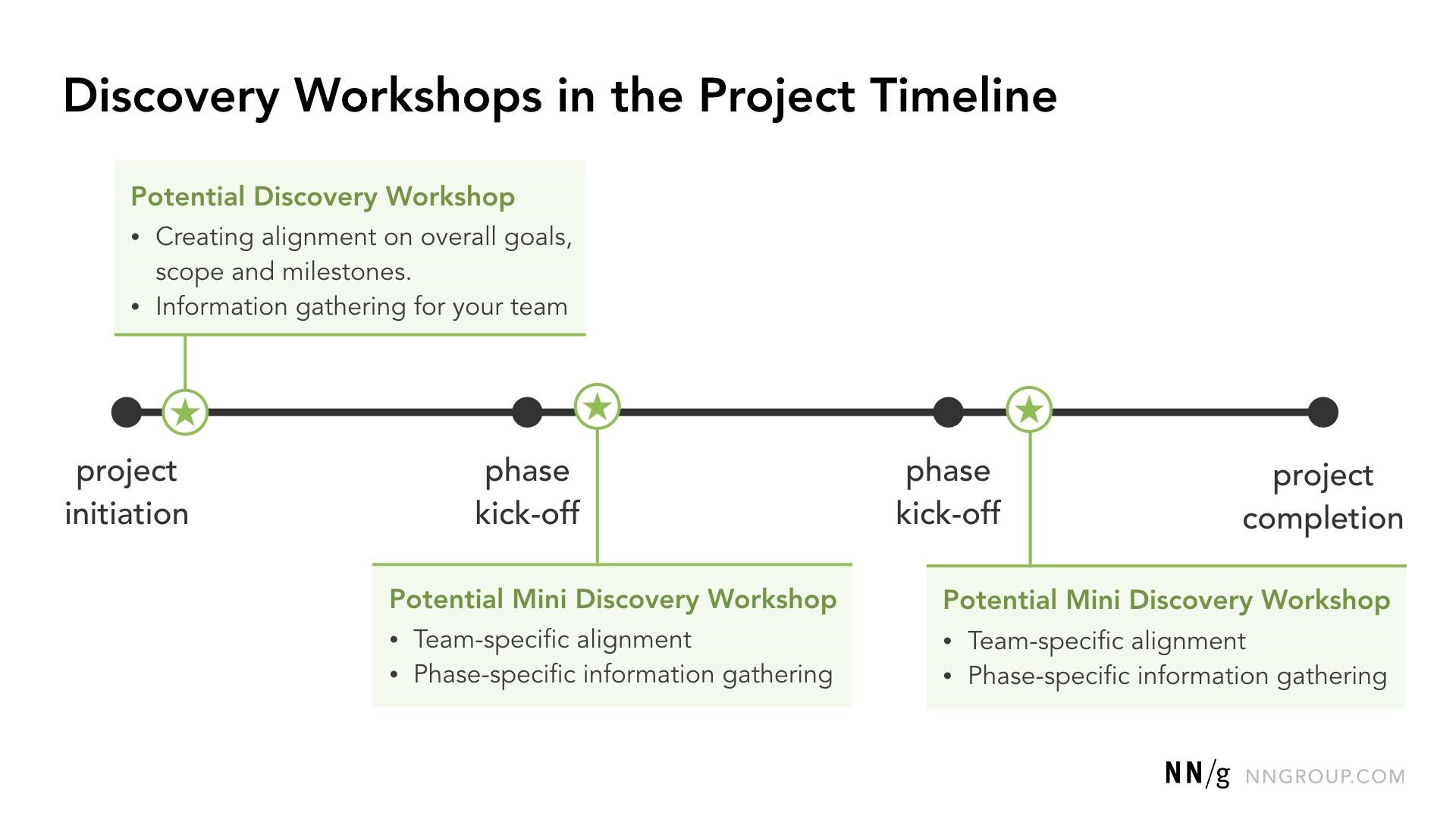

Discovery Workshops in the Project Timeline

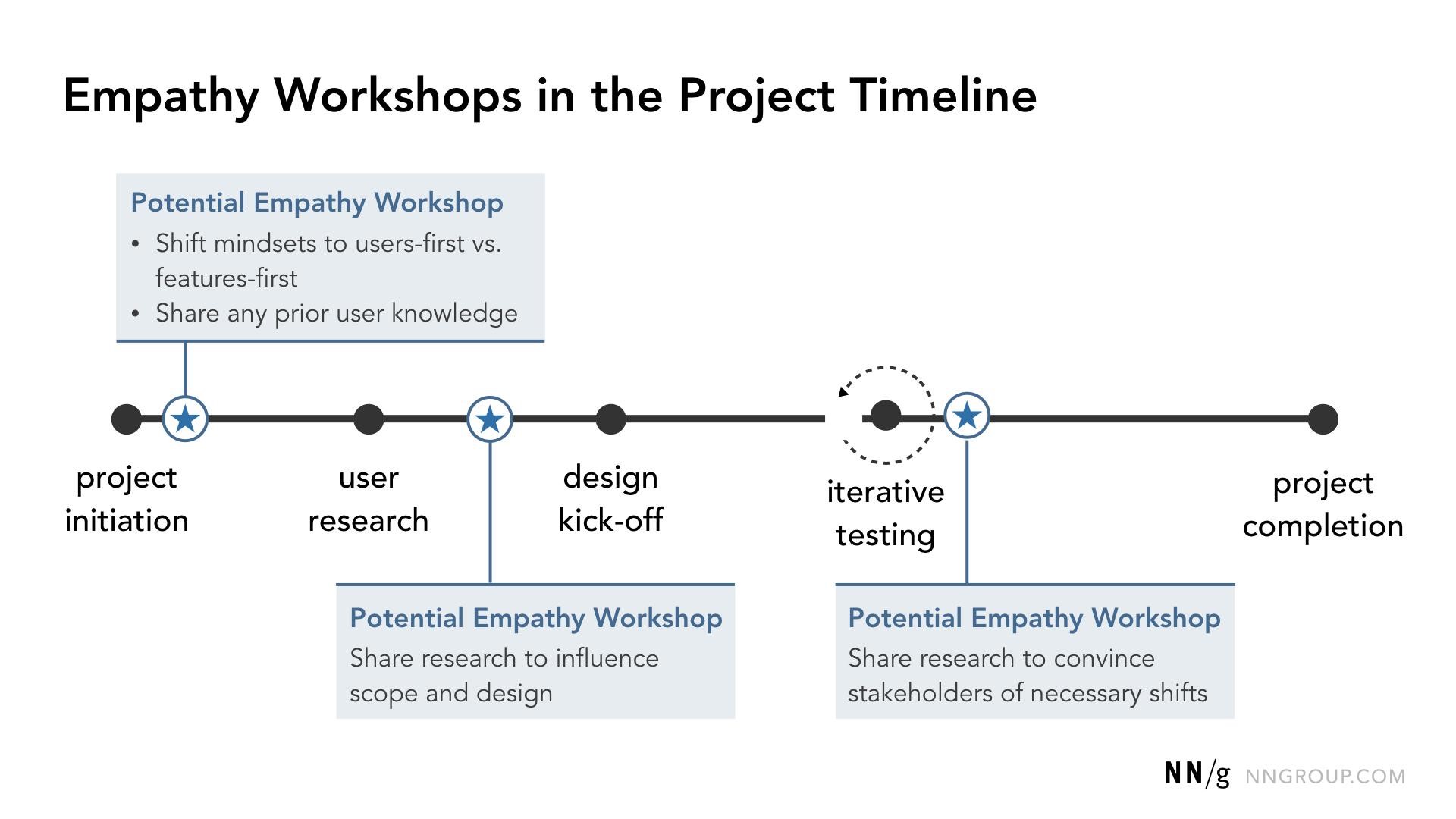

Empathy Workshops in the Project Timeline

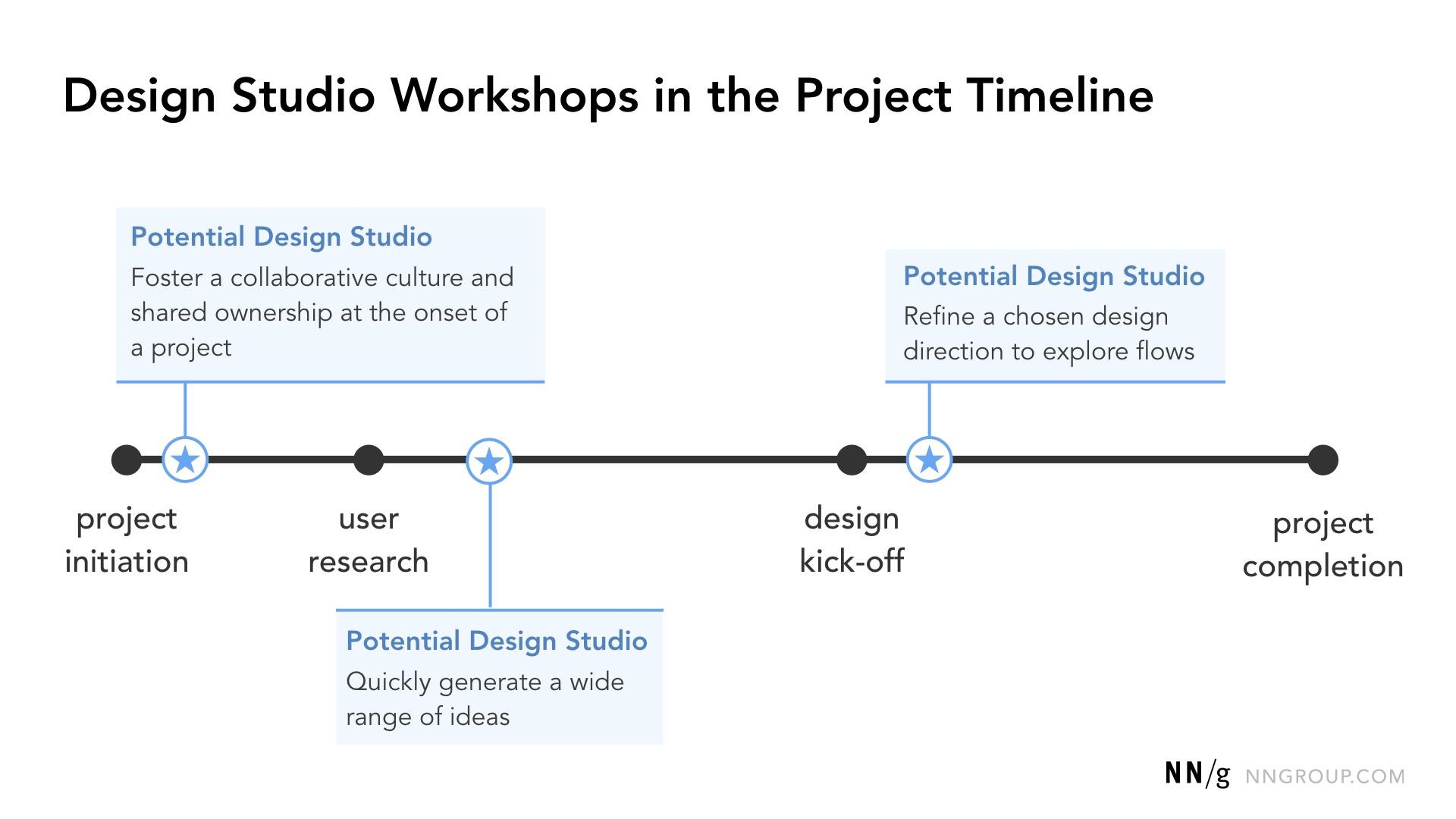

Design Workshops in the Project Timeline

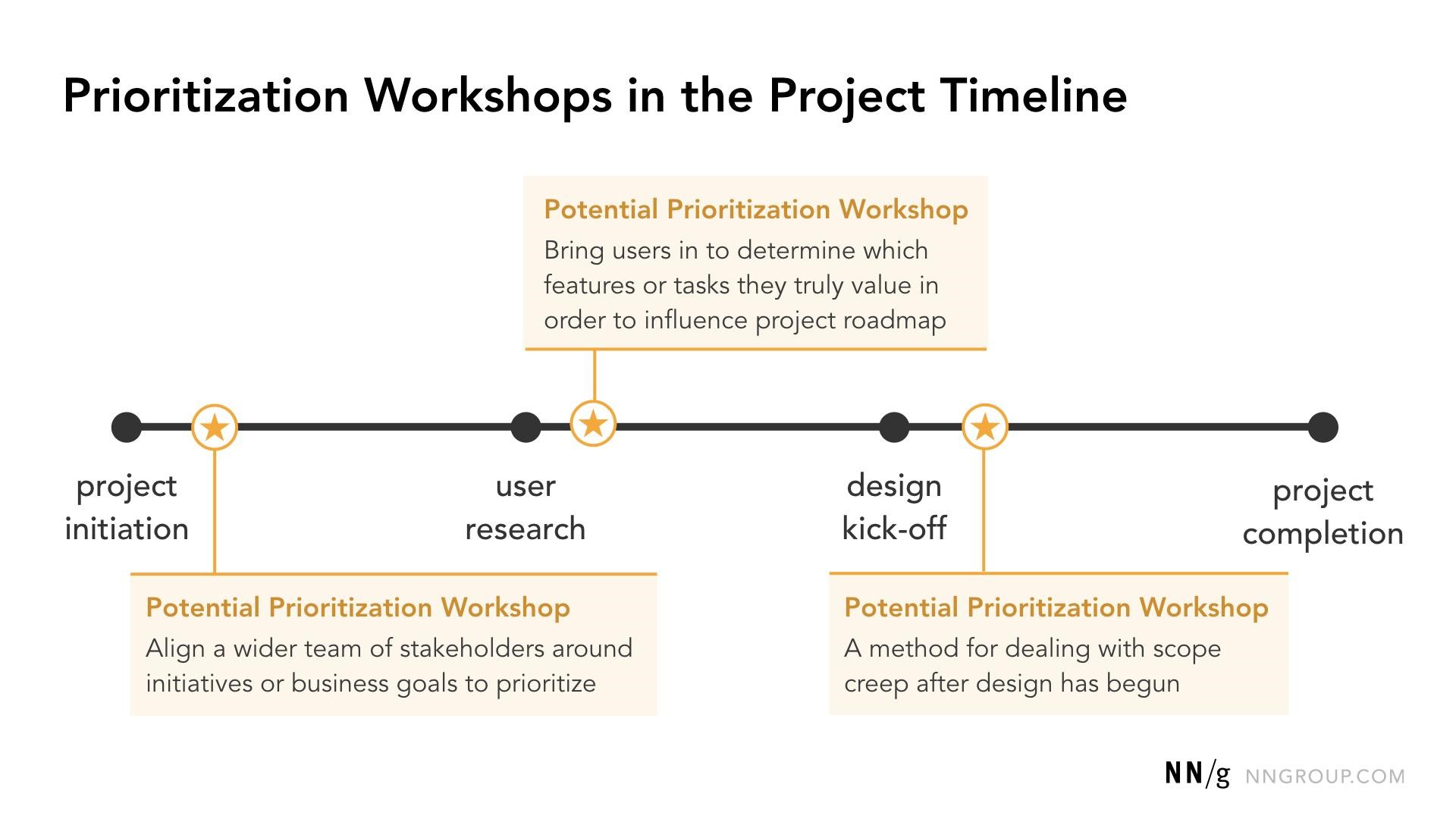

Prioritization Workshops in the Project Timeline

Critique Workshops in the Project Timeline

The Rule of Thumb

The rule of thumb is that, do NOT conduct workshops unless you have really convincing reasons to do so (specifically, all the conditions are there to afford an effective and efficient workshop).

More often than not, interview meetings and work sessions suffice.

What Workshop is NOT

1. Workshop is (Almost Always) Not Your First Step

As stated earlier, workshop is not something you jump into just because you suddenly have that idea or because you just feel like it.

An effective and efficient workshop requires proper planning and designing, which is often a bigger effort than the workshop itself.

More often thannot, something you can jump right into is likely a work session, which is a more flexible format where people talk and go through ad-hoc activities (see Core Concepts).

2. Workshop is Not Design Thinking, UX Design, or Design

Workshop is one of hundreds (if not thousands) of methods used in practices commonly denoted as “design thinking”, “user experience (UX) design”, or simply “design.”

If someone is telling you that a proposed workshop is any of those, be cautious with the understanding that:

- Workshop is NOT representative of any kind of design practice

- Workshop can NOT replace a well-defined design process for solving problems

- Workshop is NOT always necessary

3. Workshop is Not Problem Solving

Hoping to solve a problem through a workshop is like hoping to find a partner for life with just one date——possible (and delightful if achieved), but highly improbable.

When problems are well defined and have been explored sufficiently, it’s not only possible, but also probable to solve them through one or more workshops.

But more often than not, a workshop is the beginning of solving your problems, rather than the end of it

Workshop is the prequel to problem solving. It gives you useful clues to approach your problems. The real “solving” part of “problem solving” often comes after the workshop, with action plan and hardwork.

4. Workshop is (Almost Always) Not a Once-For-All Effort

If you have legitimate, reasonable, and compelling justification for a major workshop, chances are you need more than one.

A major workshop often derives follow-up workshops when the problems are complicated or complex.

Be prepared to have follow-ups.

5. Workshop is Not a Replacement for Research

Workshop should not and cannot replace any research work, formal or informal.

Workshop is one of many techniques to do research (often in the names of design research, user experience research, among many), but it’s in no way the one and only

Proper research is often a combination of diverse techniques, including workshop, that pave way for uncovering understanding, insight, or solutions.

6. Workshop is Not the End

Workshop can only be the means to a meaningful end that clearly defines measurable outcomes and benefits. Workshop as an end itself is what’s often called workshop theatre.

7. Workshop is Not Magic

Anyone who claims otherwise shall be subject to impeccable scrutiny.

Positioning Workshops

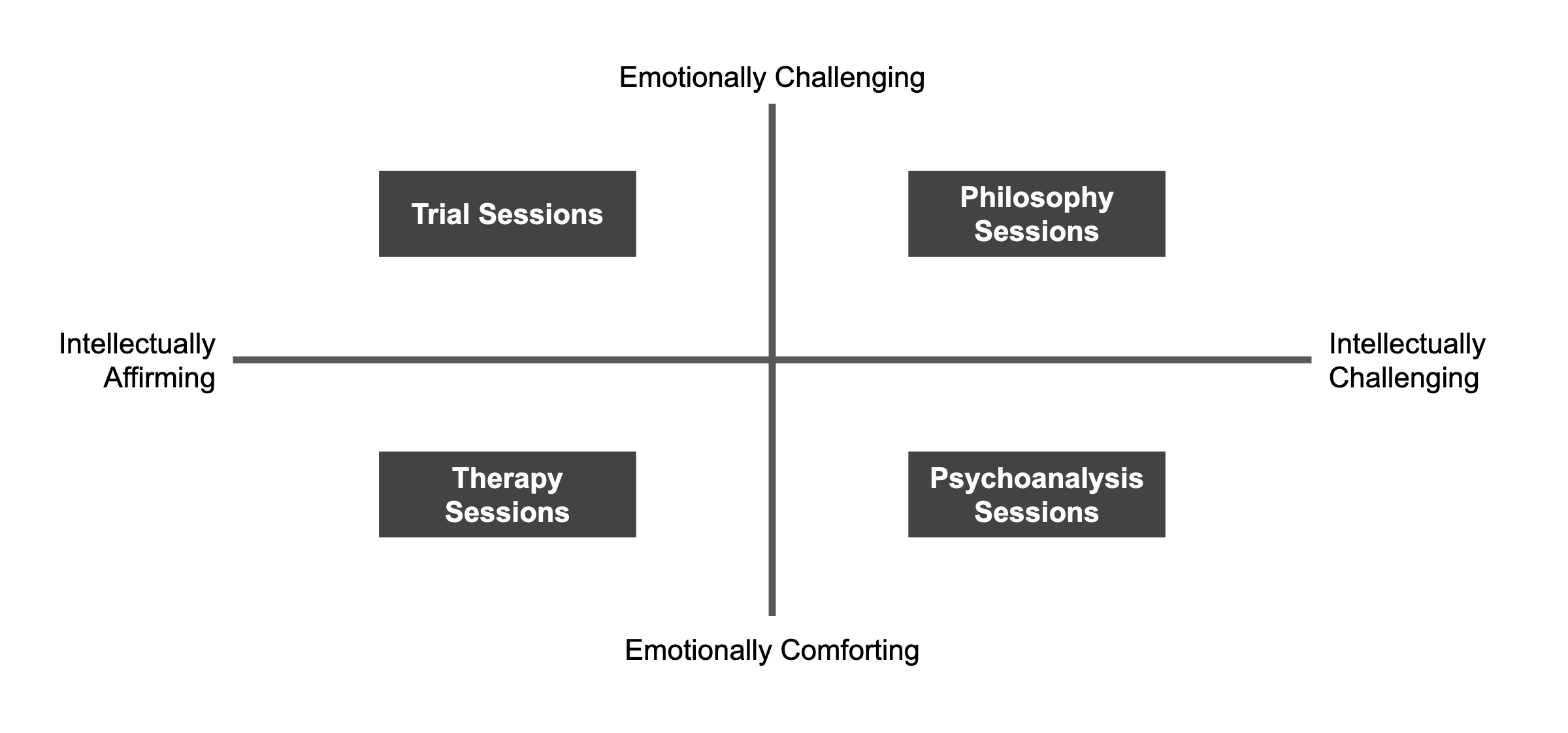

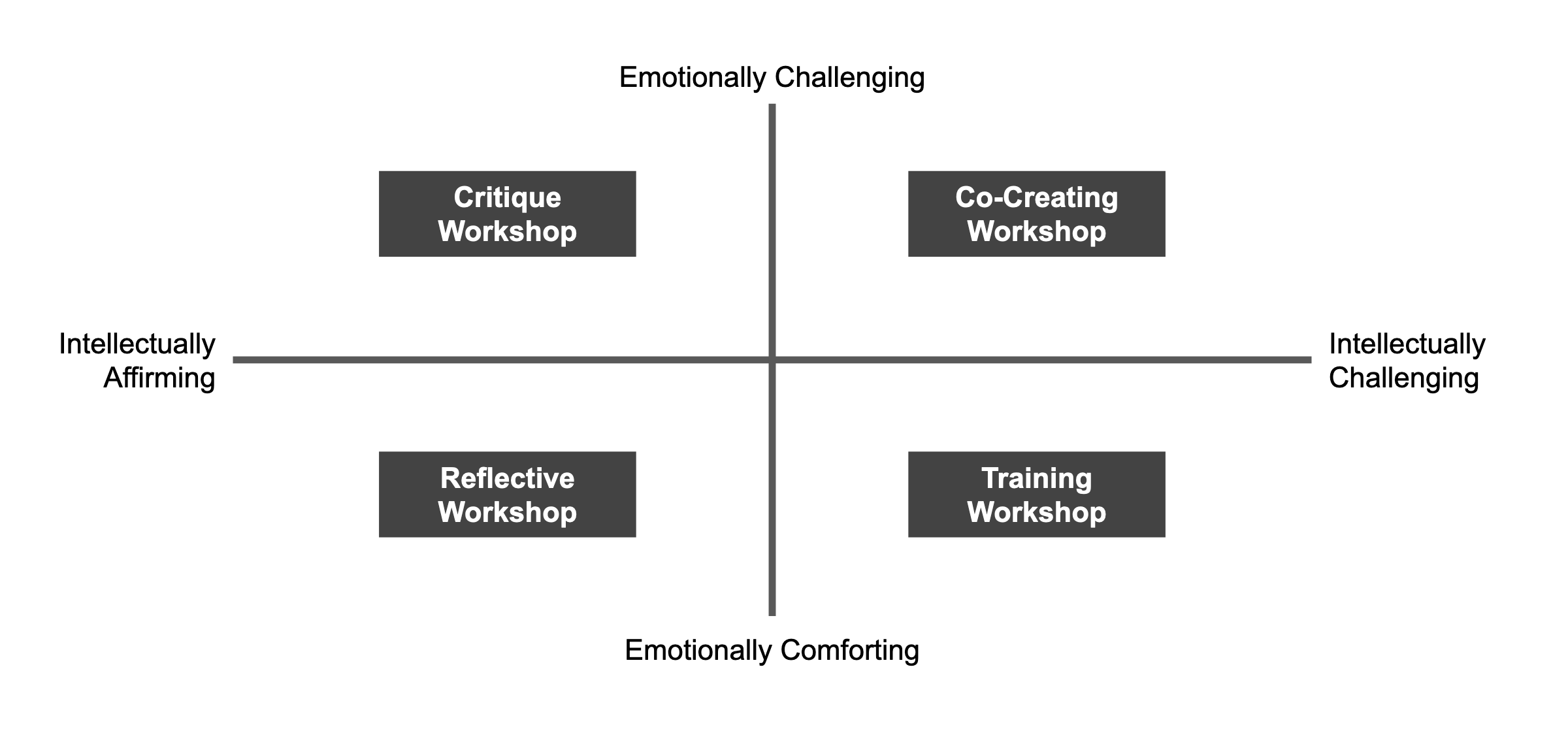

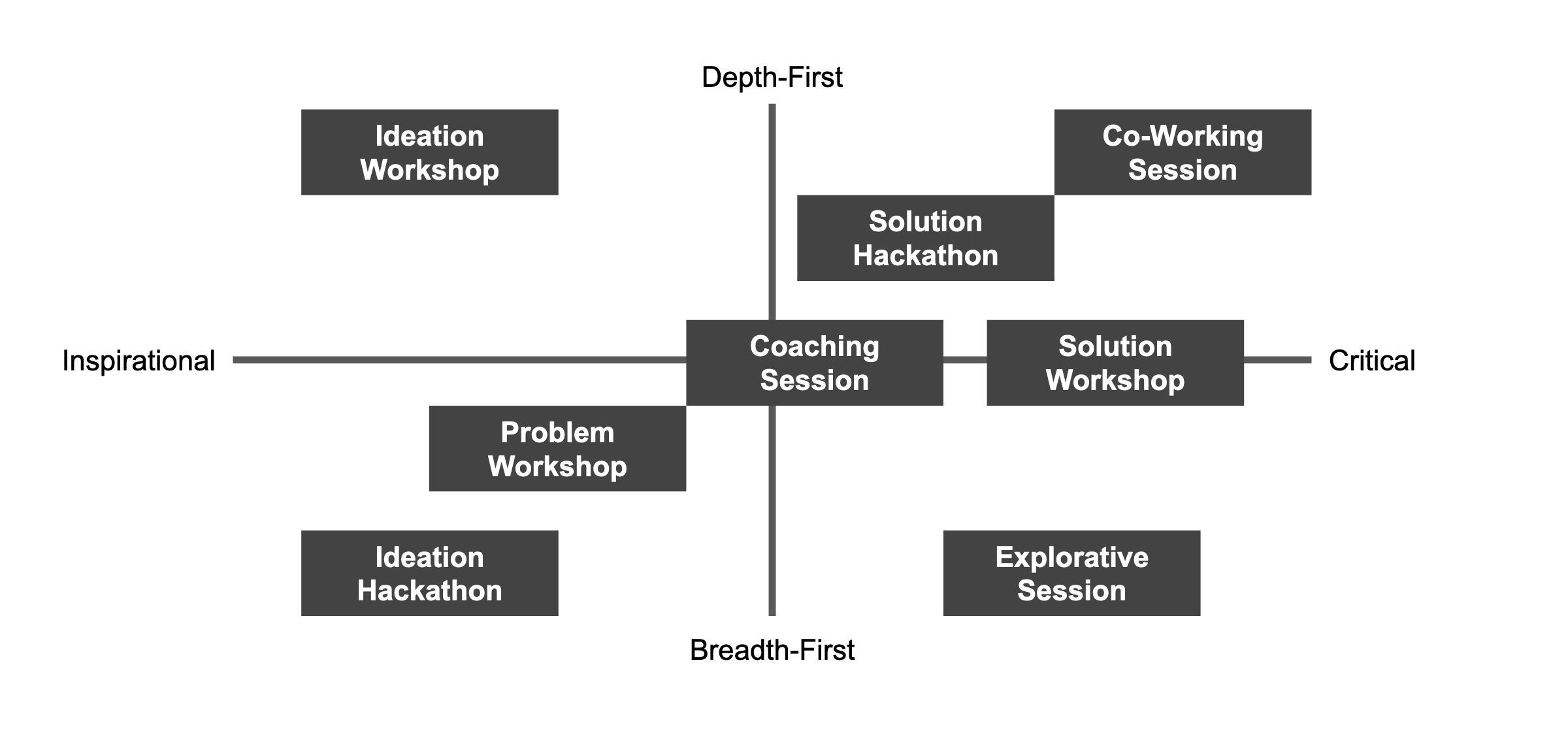

To help you put a workshop in context, here are some common framings around workshops and sessions, which may help you decide what you need in your situation.

Firstly, a session can be categorized based on its intellectual and emotional impact:

Secondly, workshop, as a more formal and specialized form of session, can be categorized on the same basis:

Thirdly, a workshop or session can vary on factors such as the extent of being inspirational or critical, as well as in its breadth and depth:

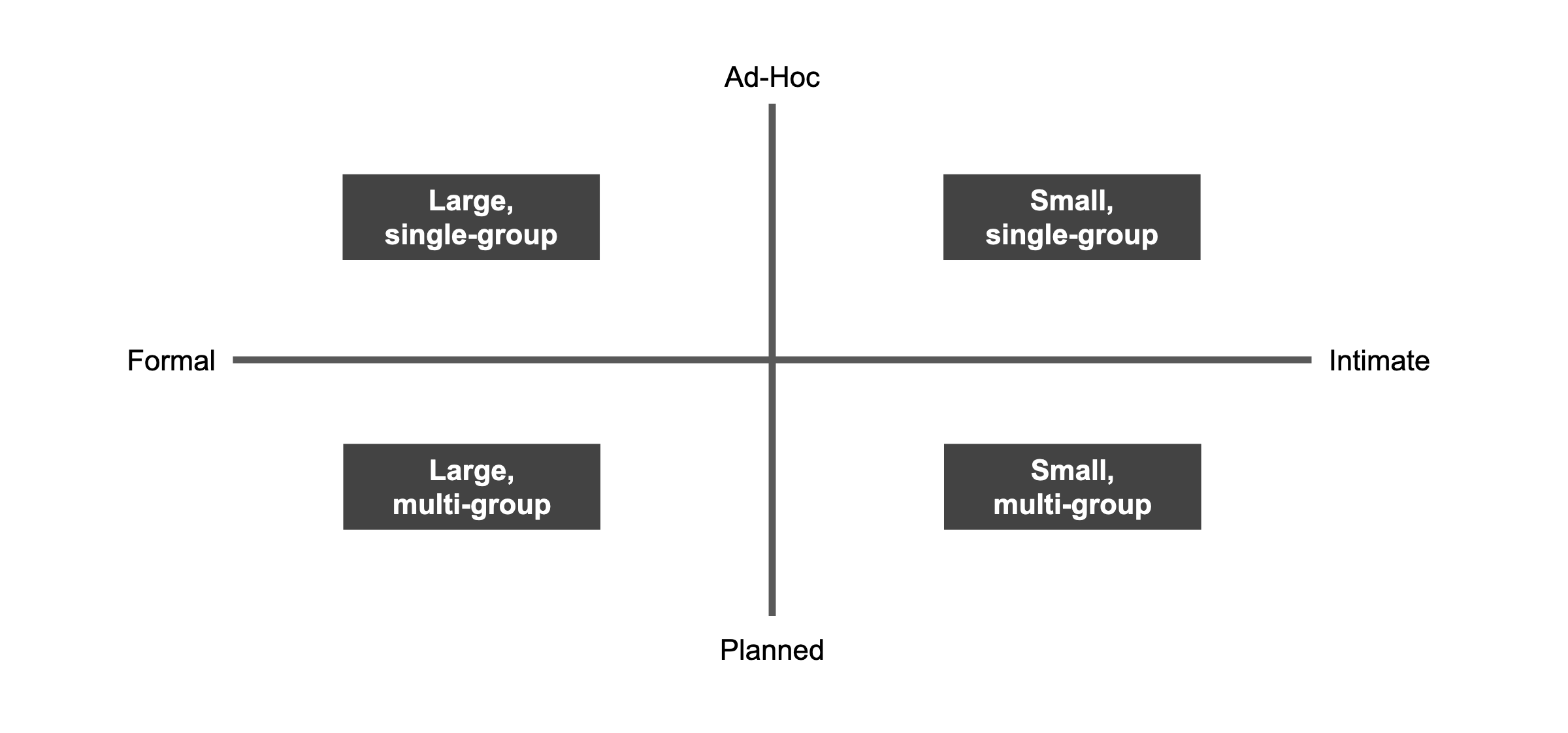

And lastly, both size and formality have impacts on the kind of format you may want to pursue:

All the above considerations and framings come down to one principle—

Understand the context before you decide on anything about workshop. Depending on your context, you may or may not need a workshop, and you may or may not need it in a specific format. Understanding your context (goals, situations, audience, etc.) is critical.

Running the Play

Before You Start

Before getting help, several considerations are worthy noting.

Planning, conducting, and analyzing a workshop is an expertise you don’t get for free. It takes time and practice to become a good planner and facilitator of a workshop.

More importantly, a workshop is often coupled with the respective business domains or professional fields related to the goal you want to achieve.

The planner and facilitator of a workshop is someone who has sufficient knowledge and experiences on both sides. As typical examples, a design workshop would often be planned and facilitated by a designer embedded in the respective project team, and a user experience researcher would conduct workshops as part of her user research effort.

Whether you decide to hire a dedicated person or do it yourself, make sure you elaborate on what kind of expertise and experience is required to increase the likelihood of implementing a successful workshop.

Conveniently, if you have in your project team a dedicated designer hired for user experience, product/service design, and/or research, chances are you could leverage her expertise for workshops, since conducting workshops is often part and parcel of a designer’s toolkit.

If you don’t have sufficient understanding to make informed decisions on whether or how to conduct a workshop, consult with an experienced designer, or hire one.

Last but not the least, if you think you need help on designing and conducting workshops, see Getting Help.

Making Decisions About Workshops

There are many questions you need to answer about workshops before you decide to do it:

- Is there a clear, achievable goal?

- Is there a consensus on that goal?

- Is there already some level of buy-in from the target audience?

- Is there basic level of trust among facilitators and target audience?

- Has general knowledge sharing between the target audience and your team already happened?

- Is there a willingness to go deeper into a particular issue?

- What makes you think workshop is the best way to achieve your goal?

- What are the potential alternatives to a workshop for achieving your goal?

You may not have all the answers to the above questions, and that’s okay.

The whole point of elaborating on those questions is for you to take the necessary thinking required to ensure you’re doing the right thing in choosing to do workshop, besides doing it right.

When in doubt, just get help.

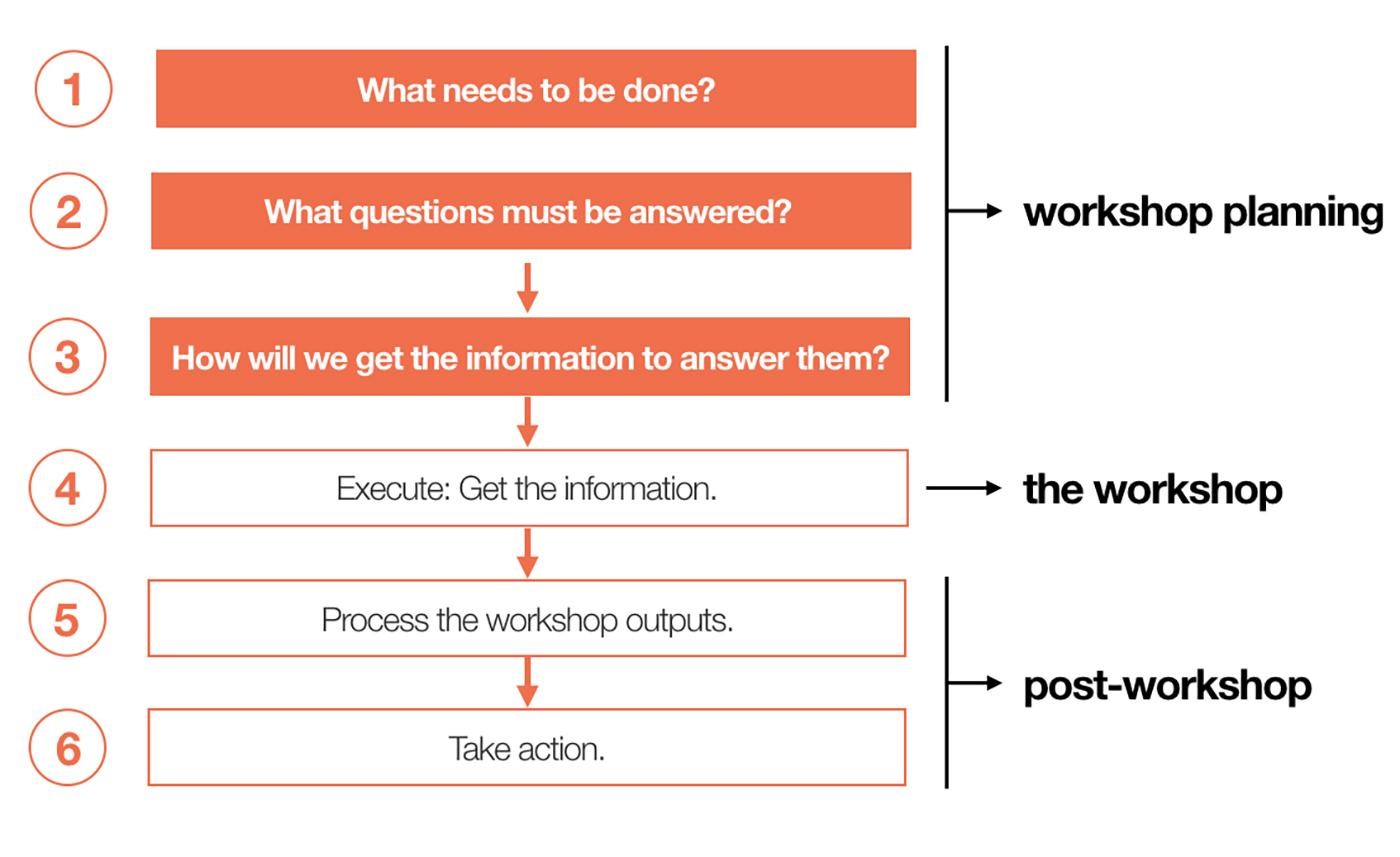

Process Overview

The whole “workshop business” concerns several distinct phases, each of which will be discussed below.

Preparing a Workshop

“Plans Are Useless, but Planning Is Indispensable.”

Contrary to the common myths, best intentions don’t guarantee results. Ideas and solutions don’t just simply happen because we do workshops. A clear goal and a focused strategy are critical to workshop success.

Three Building Blocks of a Workshop Agenda

1. Goal

Define the intended outcome of the workshop, and how you measure to determine whether the goal has been met.

2. Questions

Describe the information you need to collect from the workshop in order to achieve the goal.

3. Processes

Describe the activities you need to collect the information.

Steps for Preparation

Step 1: Define the goal(s)

Write a concise description of the end goal, often in the form of an ideal end state.

Articulate the intentions:

- Is it about reaching consensus?

- Is it about gaining shared understanding?

- Is it about generating new ideas or exploring possibilities?

- Is it about gaining empathy or building relationships?

Step 2: Describe the information you need to collect

There must be a gap you can describe between the goal and the current state of the matter.

Articulate the kind of questions you need to answer in order to bridge that gap, be it about knowledge, understanding, ideas, or anything else. Those “gap questions” can be specific or broad, for example:

- Who is the target audience?

- What is the root problem?

- What does the challenge mean to different people?

- Why do we have this problem?

- What kind of metrics can we use to measure something?

- How might we do something differently?

- What do we mean when we say “good service”?

- What are the requirements for a project?

Step 3: Define and align the activities accordingly

Once you have the list of questions you need to answer through the workshop, you can look for the kind of activities that can help you get the answers in the most effective and efficient way.

There are many great references on workshop techniques and methods, including but not limited to:

Engagement Styles

Depending on the relationship between the facilitator and the participants, and between different parties of the participants, you may need to use different styles of engagement during the workshop:

| Distrusting | Trusting | |

|---|---|---|

| Conflicting Interest | Diplomat | Frenemy |

| Shared Interest | Negotiator | Collaborator |

A facilitator needs to carefully research her participants before the workshop, and elaborate on how she might engage them in different activities and on different topics.

Planned Workshop Vs. Ad-Hoc Workshop

Planned workshops often take longer to prepare, and may be more complex in terms of logistics, participants, activities, or topics.

Ad-hoc workshops are often decided upon emergent considerations or issues. Despite its name, it still takes time to prepare.

The difference between a planned workshop and an ad-hoc one can be subtle, while often it’s the complexity and scale that differentiate them:

| Planned Workshop | Ad-Hoc Workshop |

|---|---|

|

|

Formal Workshop Vs. Informal Workshop

Another way to articulate about workshops is how formal it might be:

| Formal Workshop | Informal Workshop |

|---|---|

|

|

Whereas “planned vs. ad-hoc” denotes the differences in action, “formal vs. informal” denotes the differences in feeling, albeit subtle at times.

A facilitator may use different techniques to create an atmosphere that speaks to the intended feelings.

Conducting a Workshop

Workshop Facilitation

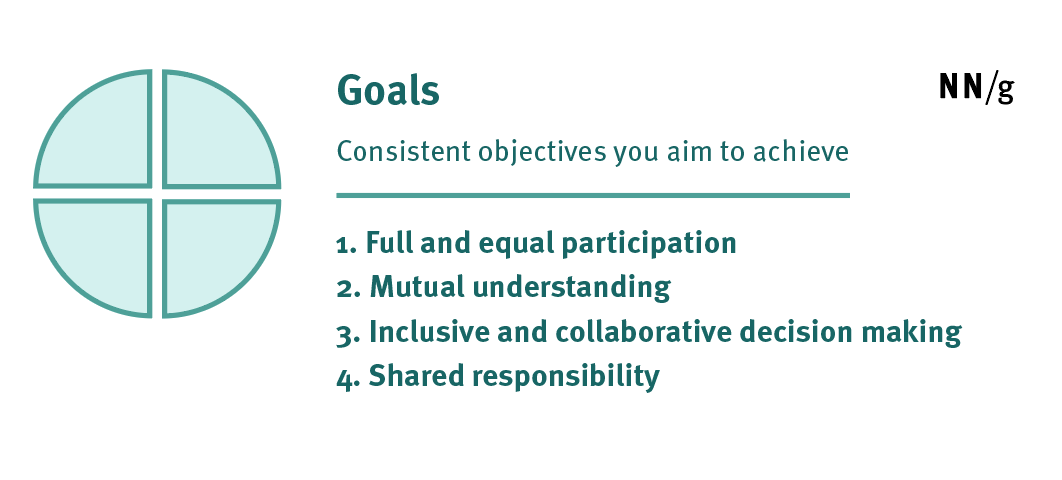

According to Nielsen Norman Group, workshop facilitation is “the act of providing unobtrusive, objective guidance to a group in order to collaboratively progress towards a goal.”

Facilitation Goals

Facilitators have their own goals, even though they carry over the workshop participants’ goals. Specifically, facilitators needs to promote full and equal participation, mutual understanding, inclusive and collaborative decision making, and shared responsibility.

Facilitation Principles

Facilitation is both art and science. You could benefit a lot from an experienced facilitator, who could implement your workshop in much more effective and efficient ways.

If you have the time and dedication to let someone inexperienced in facilitation implement the workshop, make sure you discuss with the facilitators on the following general principles:

- Always be listening

- Create an inviting space

- Welcome improvisation

- Be authentic to you and your knowledge

- Avoid giving advice

- Embrace constructive conflict

Facilitation Toolkit

Most experienced facilitators have their own toolkit ready at hand to start planning and conducting workshops.

In that regard, two things are critical to your workshop:

- Make use of the existing toolkit you have access to, and

- Take intentional effort to establish your own toolkit as you practice and learn

Facilitation Resources

Besides the References section, other useful online resources include:

Foundational Workshop Activities

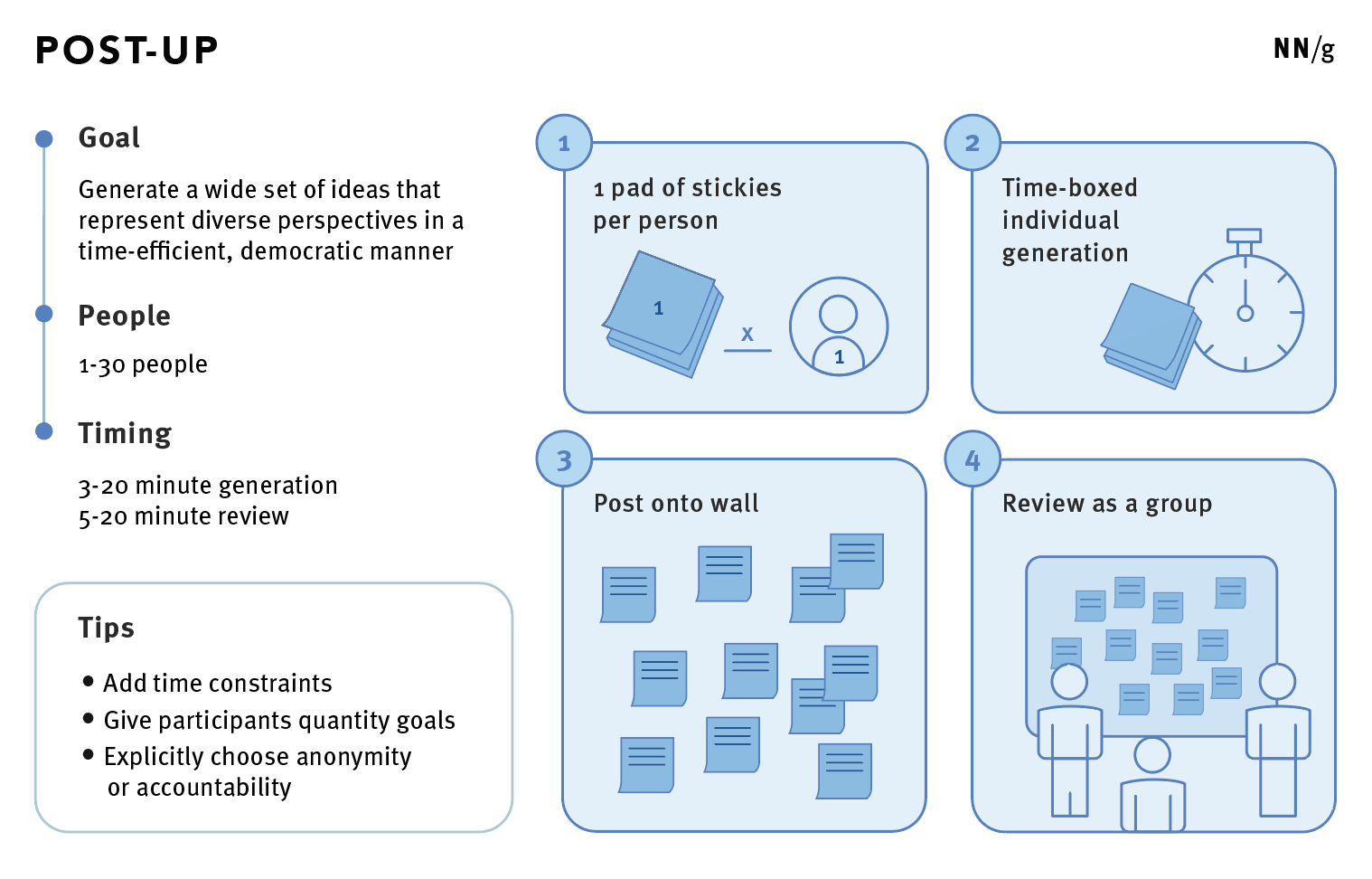

Although there are hundreds (if not thousands) of workshop activities tailored to a wide range of situations and goals, at the core of most of them are seven foundational activities (as described in Foundational UX Workshop Activities from Nielsen Norman Group):

- Post up

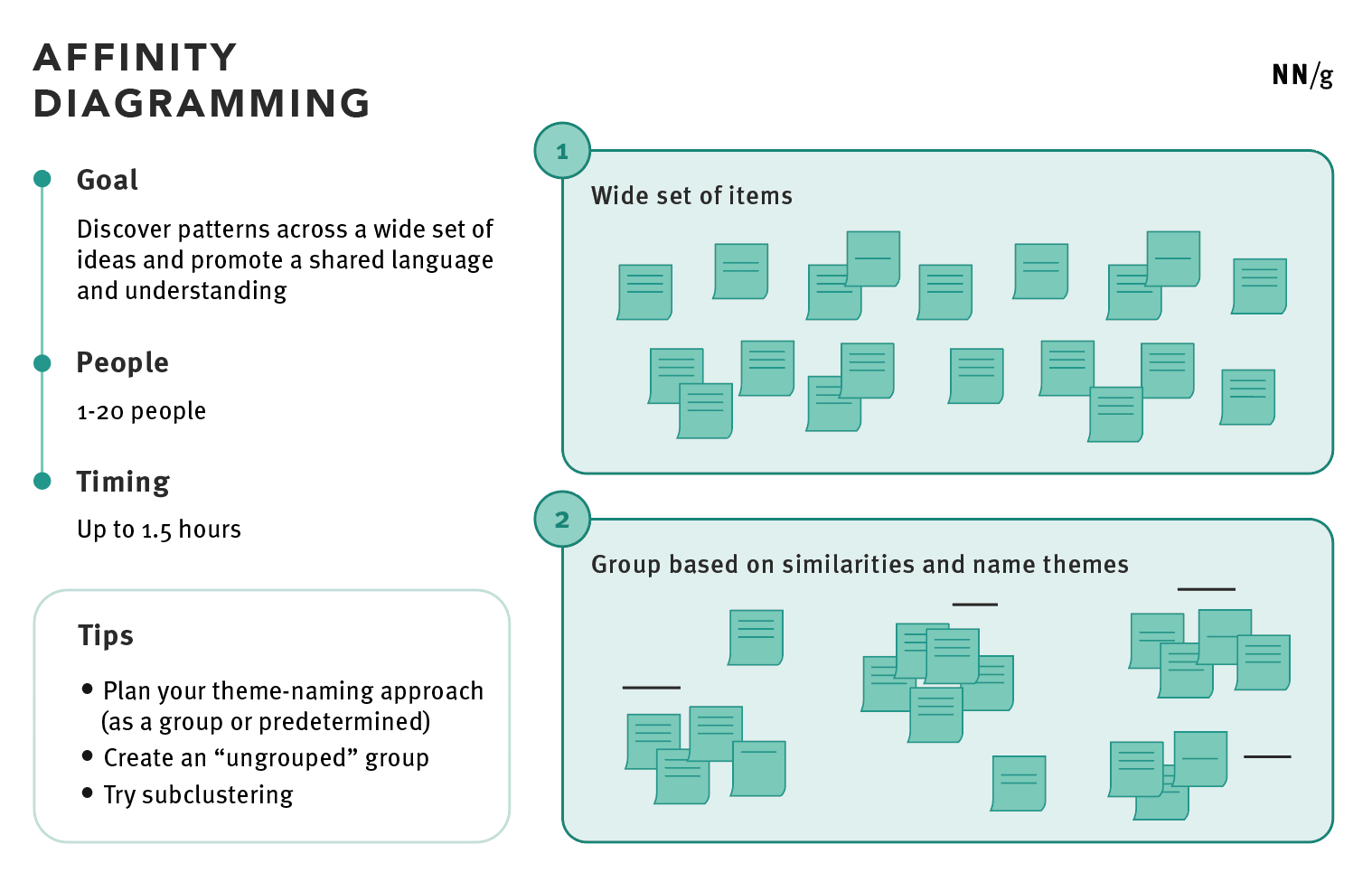

- Affinity diagramming

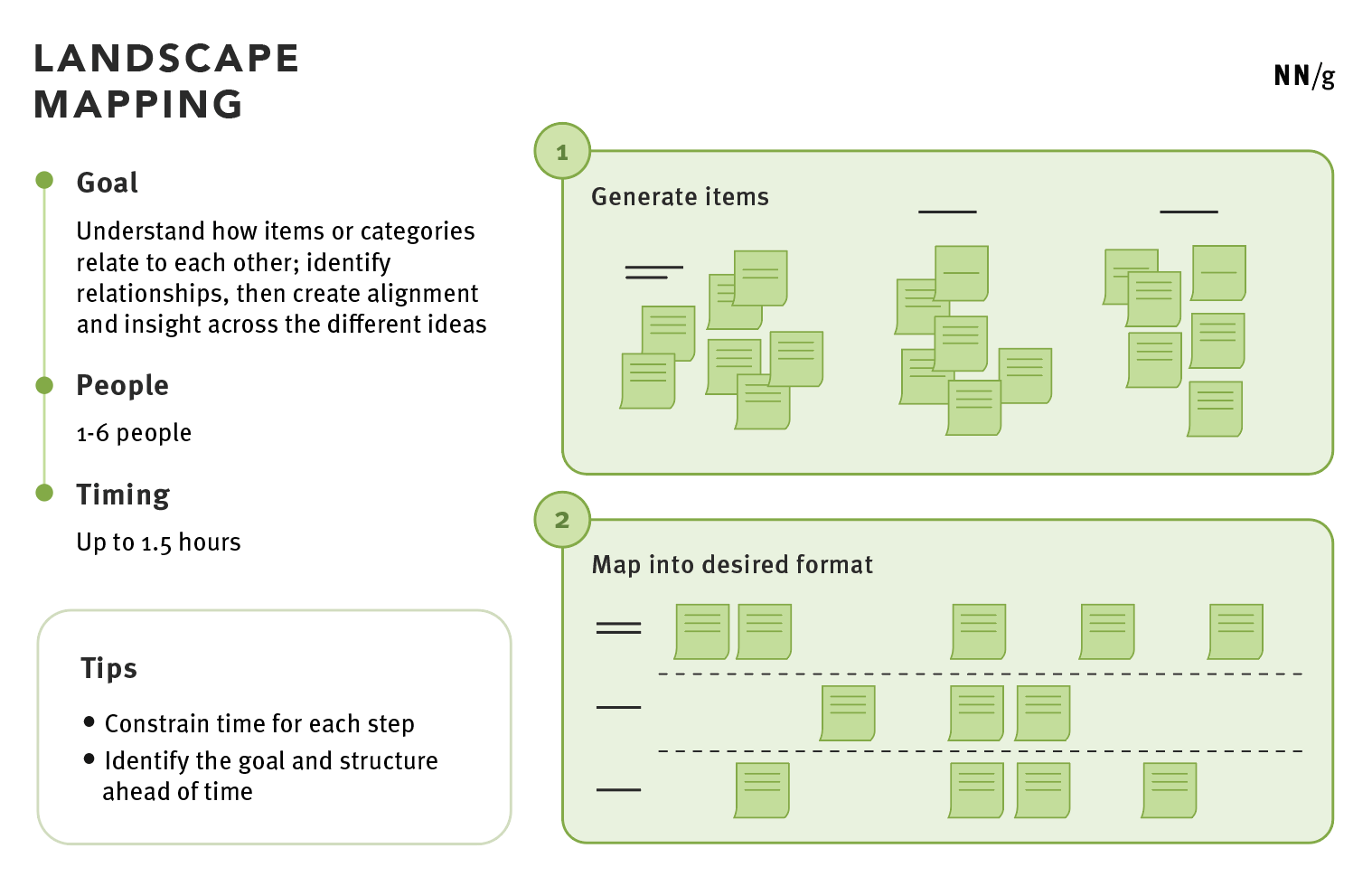

- Landscape mapping

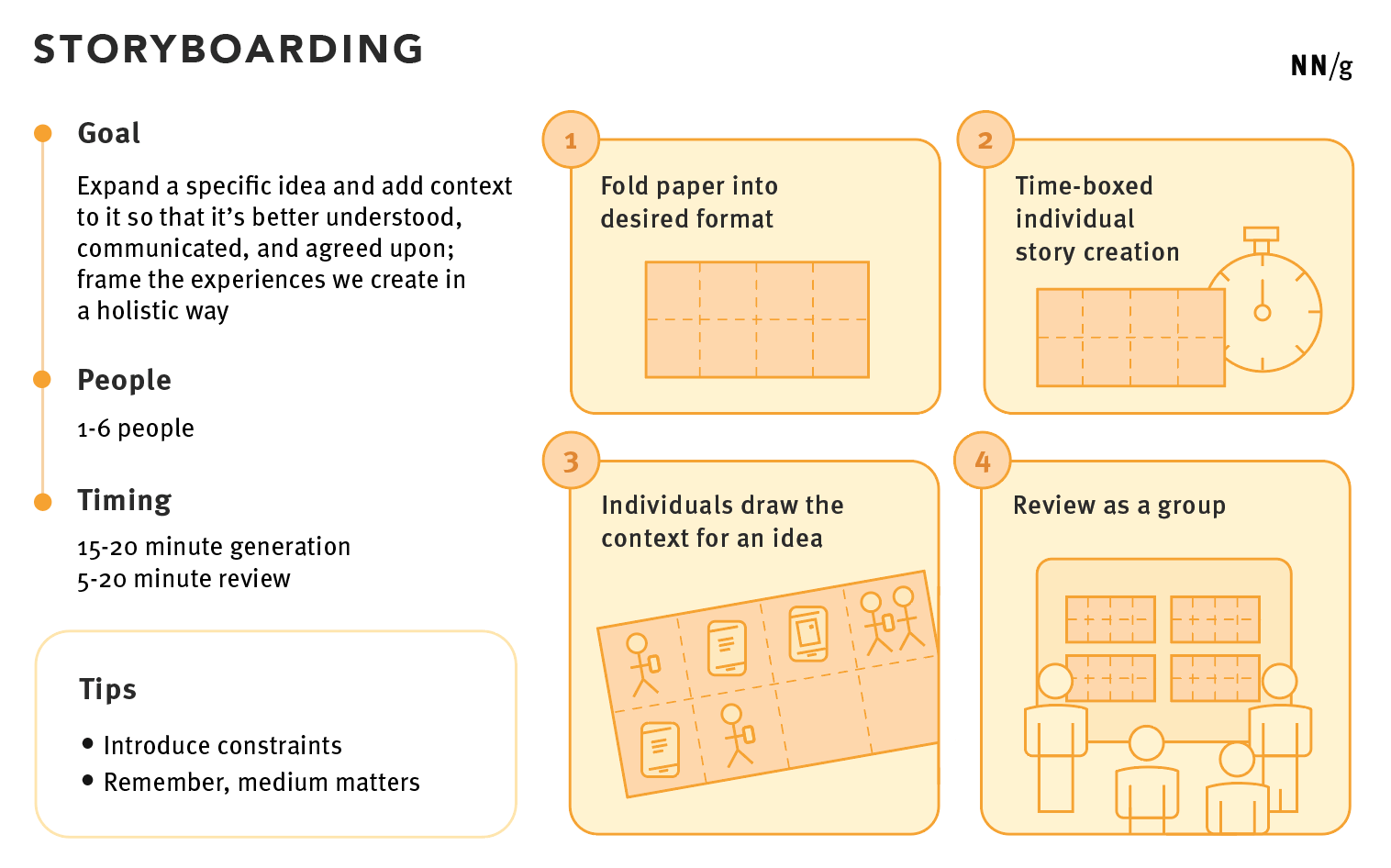

- Storyboarding

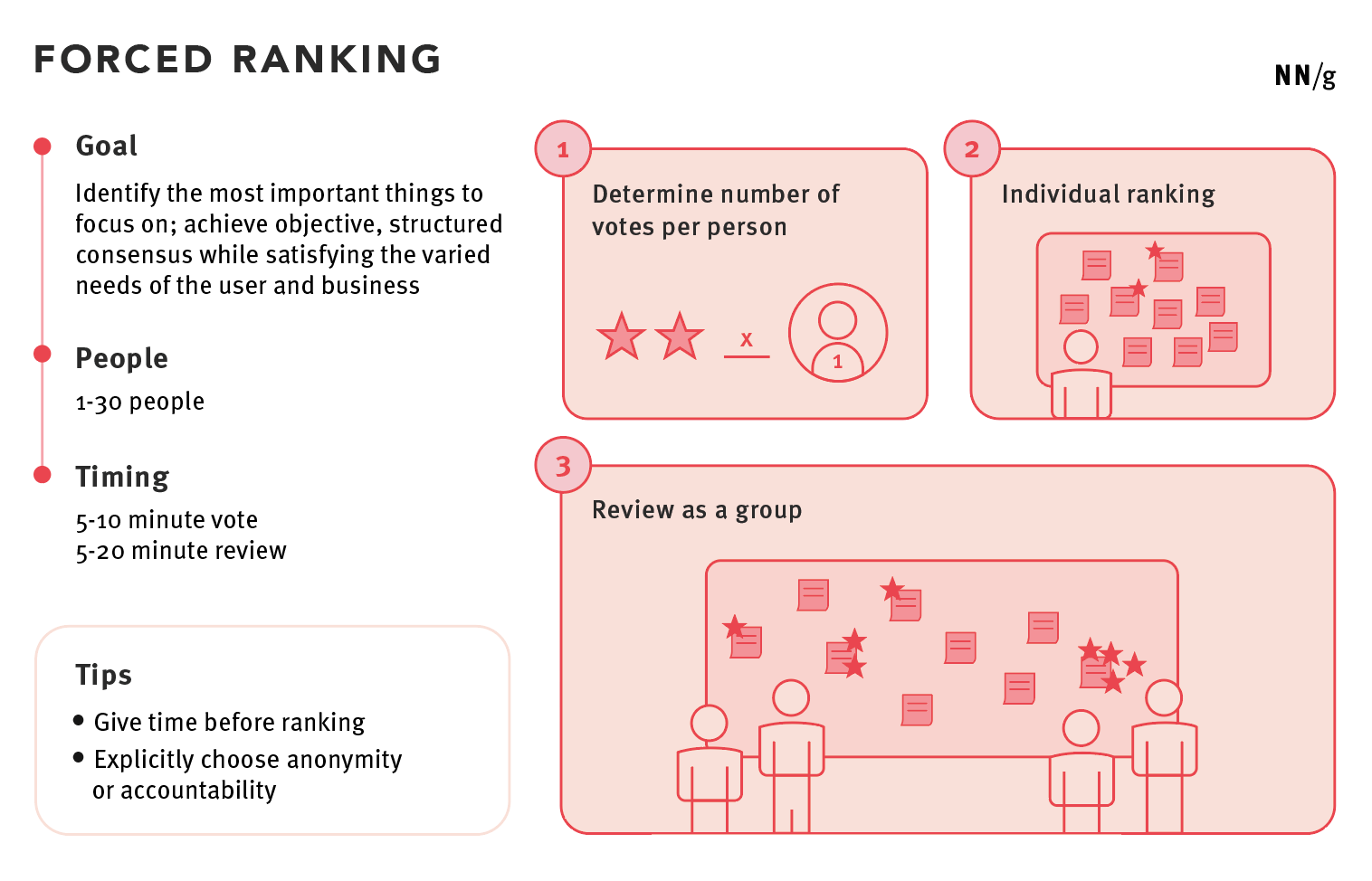

- Forced ranking

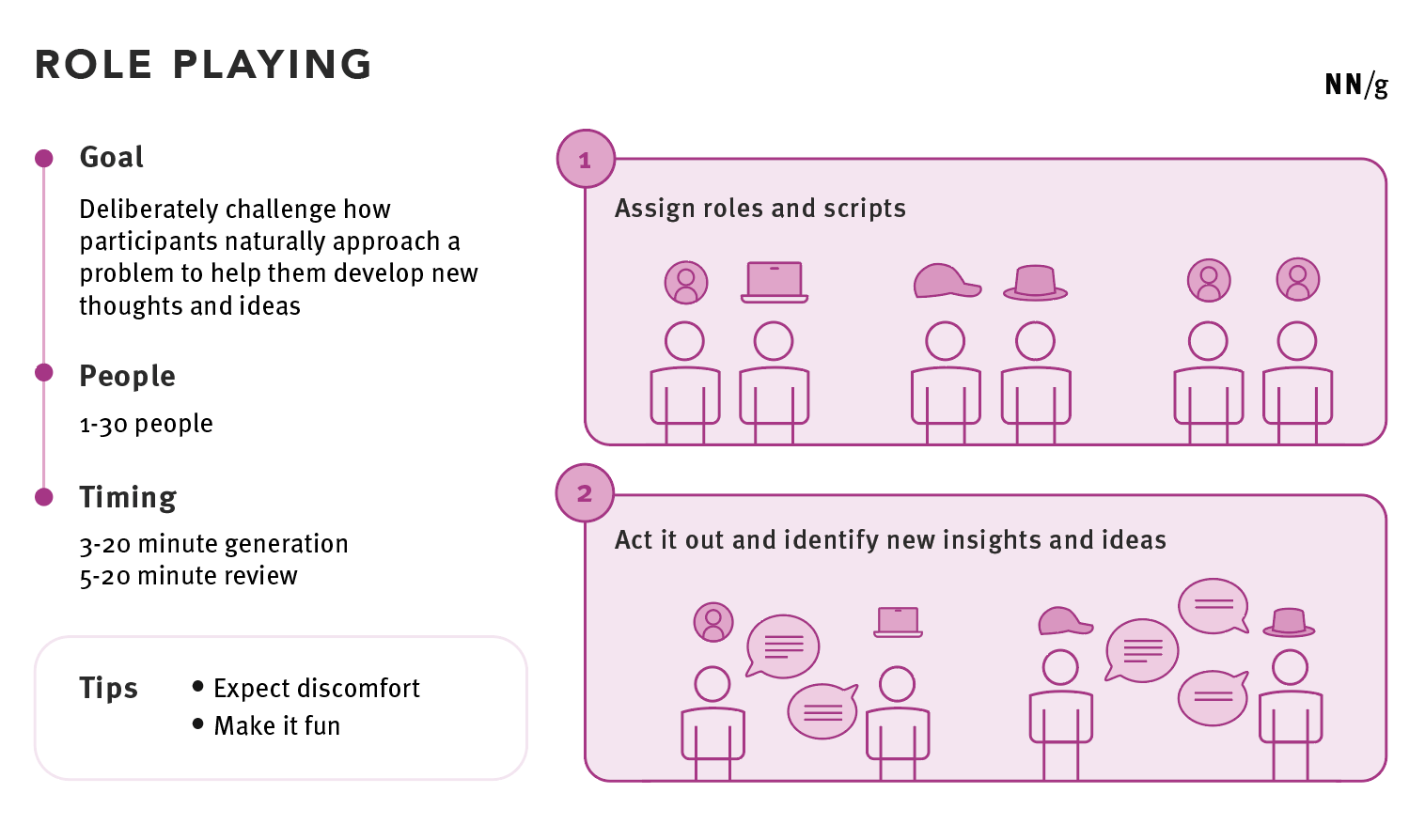

- Role playing

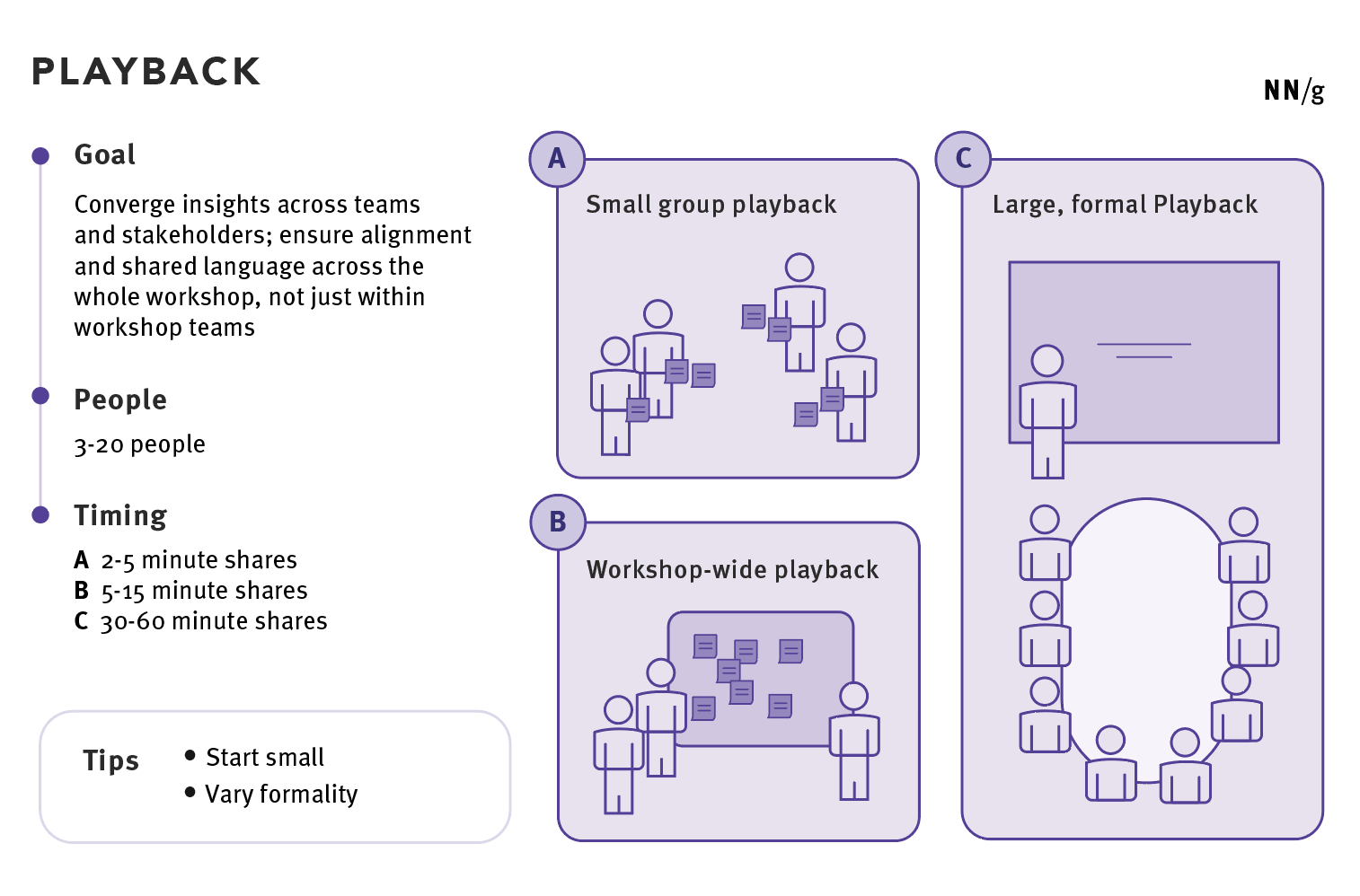

- Playback

Post Up

Affinity Diagramming

Landscape Mapping

Storyboarding

Forced Ranking

Role Playing

Playback

For more details on the above activities, please refer to the original article Foundational UX Workshop Activities.

Chances are, even when you design your own specialized activities for a workshop, you’d include elements from those foundational activities.

The Workshop Manifesto

The following manifesto is not meant to be the universal law you can’t break; however, the seven general principles below largely reflects the best practices of some experienced facilitators. They are not meant to be followed blindly, feel free to break away from them when you have compelling reasons to do so.

1. Everything is time-boxed

Start on time. Stop on time. Exceptions need to be justified.

2. Rhyming Over Timing

Propose to extend time when keeping the rhyme of thoughts is critical.

3. Writing Over Speaking

Write down your thoughts as much as you can. Only one person can speak at a time. We can all write at the same time.

4. Opinion Over Complaint

Describing the symptoms of a problem only helps so much. Bringing up your opinion on the root causes is far better.

5. Debate Over Opinion

Constructive debate yields more than the sum of different opinions.

6. Idea Over Debate

There are no bad ideas. All ideas matter equally. Proposing ideas to solutions is the perfect outcome of debates.

7. Suspend Judgement

Result is the only judgement.

Conducting Remote Workshops

Conducting workshops remotely poses many challenges compared to the conventional face-to-face ones:

- Different logistics considerations

- Technical limitations and barriers

- Potential loss of facial expressions and body language as effective ways of non-verbal communication

- Much harder to keep and track participants’ attention

Although the general design principles still hold, conducting remote workshops requires you to take those “remote work challenges” into consideration up from the planning phase.

In remote workshops, synchronous activities and asynchronous ones have significant impact on the process and the facilitation, often more than in-person workshops do.

Therefore, the choice of tools is coupled not only with the workshop design, but also with many other considerations mentioned above.

For more information, please refer to Tools for Remote UX Workshops.

Post-Workshop

Despite what you may have heard about how an eye-opening workshop made a difference, there’s so much more than meets the eye when the workshop is done. Without proper analysis and synthesis on the information collected from the workshop, it’d be hard to imagine how anything bigger than a trivial individual task could make a real difference in solving your complex problems.

There are three major steps to go after a workshop:

- Analyze and synthesize the information collected from the workshop

- Create post-workshop report to summarize the findings

- Take action upon the result of the analysis and synthesis

Analyzing and Synthesizing Information

Whatever that’s collected from a successful workshop often has descriptive and diagnostic value. But to gain actionable insights that have predictive and prescriptive value, you need to go further through analyzing and synthesizing what you have learned.

There’s no action without a judgement. Decisions have to be made based both on empirical evidence and on veteran expertise. While the former is often the result of a workshop, the latter amounts to a combination of what you collect and how you interpret it.

Since analysis and synthesis are worthy topics of their own, consider getting help or referring to other related plays

Creating a Post-Workshop Report

A post-workshop report is used to:

- Brief the stakeholders (regardless of whether they’ve participated in the workshop)

- Summarize the workshop and its findings

- Interpret and propose the implications of the findings

- Recommend actionable next steps

Accordingly, such a report needs to include at least the following sections:

- A summary of the workshop: what happened, when, where, and why

- The findings of the workshop: what information has been gathered

- Analysis and synthesis of the findings: what the implications are

- Action plan or recommendations: what are the next steps

Taking Action

The workshop, its findings, and its implications are the evidence that you and your team are taking an evidence-based approach to make decisions and solve problems.

Therefore, you must always be able to associate your decisions with the workshop. You must always be able to refer to something about the workshop to justify the related decisions being made.

The best evidence of your having done a worthy workshop is the confidence you have in making decisions that follow.

Workshop Tools and Materials

Facilitation Materials

Workshop materials often come in handy, as mentioned in Facilitation Toolkit.

In many cases, you barely need anything more than stickies, papers, pens, laptop, projector, and a few online tools of your choice.

Facilitator Cards is a great resource to start with planning.

Service Design Toolkit provides useful downloadable materials for use in workshops related to service design, user experience design, and user research.

Online Tools

There is a wide range of popular online tools that may be useful for workshop activities. Even for in-person workshops, appropriate use of online tools can greatly reduce the amount of time-consuming manual work and therefore make the workshop more efficient and fluent.

Depending on your budget and the complexity of tools, you do have a wide range of choices.

Here’s a summary of common online tools:

Convention: L = Low complexity, M = Medium complexity, H = High complexity

| Diagramming | Mapping | Ideation | Voting | Prioritization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powerpoint | L | L | H | H | |

| Google Draw | L | L | H | H | |

| Google Slides | L | L | H | H | |

| Mural | H | H | H | H | H |

| Miro | H | H | H | H | H |

| Google Sheets | L | M | |||

| Excel | L | M | |||

| Visio | M | M | M | ||

| Sketch | M | M | M | ||

| Smaply | H | ||||

| Mentimeter | L | ||||

| Slido | L | ||||

| SurveyMonkey | M | L | L | ||

| Google Forms | M | L | L | ||

| Microsoft Teams | H | M | M | ||

| Slack | H | M | M |

Note: the tools listed above are for reference and consideration. To confirm your choice of tools, you also need to take into consideration relevant policies and rules of your organization regarding tool usage and privacy/security factors.

Tips and Tricks

Visual Thinking

Visual thinking and visual doing are often at the core of many workshop activities. By visualizing or materializing thoughts and ideas, participants often gain an enhanced sense of clarity that stimulates creative thinking.

The rule of thumb: externalize and materialize as much as you can. If you have a thought, write it down on a sticky note. If you want to describe a process, draw it out on the whiteboard. If you are thinking about different options or possibilities, write them down on sticky notes and put them on the walls.

In most cases, there are only three things that are of your concern: people, things, and their relationships. Use sticky notes, drawings, and writings to visualize them. Chances are you’d find previously unseen connections and/or creative new ideas.

Designer and Facilitator

Workshop facilitators could come from many different places and professions. In some cases, they come from a training background. In some other cases, they’re professional facilitators from consultancies.

In the context of solving business problems or building products and services, experienced user experience designers and product/service designers are also likely to be good facilitators, since designing and conducting workshops is part of their job.

In most cases, it’s a good idea to consult with an experienced user experience designer or product/service designer about your workshop. Beware that those designers may have different job titles, such as business solution architect, analyst, or even developer. Someone who’s actually working on user experience design or product/service design is likely to have workshop experiences.

Improv Games

Most ice-breakers and warm-up activities derive from improv games in one way or another.

It’s always a good idea to learn a little bit about improvisation, either for business or for creative purposes.

Creative Thinking

Both in groups or individually, creative thinking is critical to exploring problems and solutions. A workshop facilitator is also a creative thinker, and, with proper guidance and facilitation, participants can also engage proactively in creative thinking.

Related Plays

Next Steps

As long as a workshop serves a tangible purpose, it is almost never the end of your effort. Taking actions upon a successful workshop could mean many things to you:

- It may become necessary to have follow-up workshops

- The workshop and its implications may derive side projects or even major ones

- What you learned may change the direction of existing projects or strategies

It’s up to the stakeholders of the workshop to use good judgement and decide on the next steps.

After all, what could be more disheartening than a great workshop followed by inaction or indifference?

Getting Help

As repeated frequently above, do NOT assume anyone can pull off an effective and efficient workshop with minimal expertise and experience. Facilitation and workshop design are multidisciplinary practices that most people are often not exposed to, and it takes time and effort to practice effectively and efficiently.

Whenever in doubt, get help from:

- Online resources such as Nielsen Norman Group

- Experienced facilitators and/or designers

- Service Innovation Centre of Excellence (Transport Canada Only)

To contact Service Innovation Centre of Excellence

Terms of use

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

All quotes used above, unless otherwise stated, are taken from the following resources:

Workshop

How to Create a UX Workshop Agenda (Video)

Tools for Running Remote UX Workshops (Video)

Top 5 Mistakes in Running UX Workshops (Video)

What Makes a Virtual Conference Work? (Video)

UX Workshops vs. Meetings: What’s the Difference?

5 UX Workshops and When to Use Them: A Cheat Sheet

Foundational UX Workshop Activities

A Model for Conducting UX Workshops and Exercises

Planning Effective UX Workshop Agendas

Facilitation

A 4 Minute UX Workshop Facilitator's Guide (Video)

Facilitating UX Workshops with Stakeholders in the Room (Video)

Facilitating an Effective Design Studio Workshop

Techniques

UX Workshop Energizers and Icebreakers (Video)

The "Parking Lot" in UX Workshops: Friend or Foe? (Video)

How to Prioritize Ideas from UX Brainstorming Sessions (Video)

Remote Ideation: Synchronous or Asynchronous? (Video)

The Science of Silence: Intentional Silence as a Moderation Technique

Parking Lots in UX Meetings and Workshops

The Diverge-and-Converge Technique for UX Workshops

How to Run a Journey-Mapping Workshop: A Step-by-Step Case Study

Journey-Mapping Approaches: 2 Critical Decisions To Make Before You Begin

The 5 Steps to Service Blueprinting

The 5 Steps of Successful Customer Journey Mapping

The Discovery Phase in UX Projects

Troubleshooting Group Ideation: 10 Fixes for More and Better UX Ideas

How to Get Stakeholders to Sketch: A Magic Formula

Remote Customer Journey Mapping

Remote Ideation: Synchronous vs. Asynchronous

Dot Voting: A Simple Decision-Making and Prioritizing Technique in UX

- Date modified: